This article is enlarged from a chronology originally printed for an exhibition at L.A.con III, the fifty-fourth annual World Science Fiction Convention, 29 August–2 September 1996, at the Anaheim Convention Center, Anaheim, California. It was originally published in Yarf! #46, January 1997. Yarf! published it separately online, where it has been a valuable Furry historical reference for fifteen years, with links to it from Wikipedia, WikiFur, the Furry News Network, and many other websites.

In February 2012, Yarf! disappeared without warning from the Internet, and all the links to this chronology stopped working. To restore it to the Internet, Flayrah has agreed to reprint it, slightly revised and with illustrations.

There is no single specific date or event that can lay claim to being the birth of furry fandom. However, there is general agreement that it was around late 1983 or early 1984 that furry fans coalesced out of SF fandom and comics fandom and began an independent identity.

Due to the practice in the comic-book industry of dating one to three months in the future, the dates of the comic books listed here may be a month or two later than their actual appearances.

To indicate significant geographic centers of furry fandom, the home cities have been listed of active fans. Entries without cities indicate that the individuals named have not been active in furry fandom.

The goal of this chronology is to list the “first” and the “most influential” entries in the many aspects of furry interest. Many other favorites could be added to each category: novels such as Mark Rogers‘ Samurai Cat series; movies such as Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective; TV series like the animated TaleSpin; comic books like Eb’nn, Red Shetland, Space Beaver, and Wild Life; fanzines like Hunca Munca!; MU*s like Animal Nation, FurryFaire, FurToonia, Redwall MUCK, and Tapestries. It was not our intention to slight anything. Please consider this chronology in the nature of a brief encyclopedic summary. A detailed history of furry fandom is yet to be written.

September 1966: Osamu Tezuka‘s Kimba the White Lion begins U.S. syndicated television broadcasting (through the late 1970s). It introduces such thought-provoking concepts as royal lion cub Kimba’s search for a way for well-meaning carnivores to live in friendship with herbivores without starving to death, and to get humans to take intelligent animals seriously as social equals.

September 1967: The Amazing 3 comes to America. Made in Japan as W 3 (for Wonder 3) by the same studio that made Kimba the White Lion, for broadcast there on the Fuji TV network in June 1965, this lower-budget TV cartoon series is in black-&-white, in more limited animation, and more limited American distribution; nevertheless it attracts fans with its story of three cute animals who are really space aliens who could destroy Earth.

It is dubbed into English by Copri International in Miami using college students, local radio DJs and little-theater actors as voice cast, and distributed by Erika Film Productions, Inc. Due to its syndicated nature, it plays in individual cities from September 1967 to (the last known market) April 1975.

Young Kenny Carter discovers that Captain Bonnie Bunny, Corporal Ronnie Pony, and Lieutenant Zero Duck are aliens transformed into Earth animals to decide whether humans are too warlike to be allowed into the galaxy. If they decide against humans, they have a “solar bomb” (alternately called a neutron bomb and an anti-proton bomb) to destroy Earth. Although the animals are supposed to only observe, Kenny talks them into using their superior science to secretly help his older brother Randy in his secret-agent missions for the Phoenix Bureau of Peace Enforcement.

The Amazing 3 runs for 52 episodes, but due to its poor production values and ownership by a minor distributor, it disappears as soon as its 52-episode season ends in each city. According to one website, it was shown in Melbourne, Australia from April 1969 at 4:00 p.m. on Channel 9, so presumably Erika had the rights to distribute it to any English-speaking market. A few 16 mm film prints exist with title cards for KCOP, Channel 13, in Los Angeles.

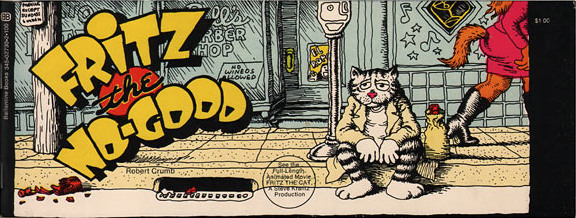

1968-1972: Robert Crumb‘s Fritz the Cat is the first “adult” funny-animal series to gain public attention, in various underground comix and especially Ballantine Books’ mainstream editions starting in October 1969, climaxing with Ralph Bakshi‘s animated feature in April 1972 — which so displeases Crumb that he kills off Fritz in a final June 1972 story. The 1972 Crumb-covered Funny Aminals [sic] is another influential underground example of funny animals featured in “mature” situations.

1971–1972: Dan O’Neill and his “Air Pirates” (Gary Hallgren, Bobby London, Ted Richards) carry on their underground-comix “guerrilla war” against the Disney morality, publishing pornographic parodies of popular Disney 1930s and 1940s comic books (Air Pirates Funnies, Dan O’Neill’s Comics & Stories, The Tortoise and the Hare), until stopped by court order. This reinforces the awareness that funny animals can appear in adult situations as well as children’s stories.

1971–1972: Dan O’Neill and his “Air Pirates” (Gary Hallgren, Bobby London, Ted Richards) carry on their underground-comix “guerrilla war” against the Disney morality, publishing pornographic parodies of popular Disney 1930s and 1940s comic books (Air Pirates Funnies, Dan O’Neill’s Comics & Stories, The Tortoise and the Hare), until stopped by court order. This reinforces the awareness that funny animals can appear in adult situations as well as children’s stories.November 1972: Richard Adams‘ Watership Down, a dramatic fantasy about “realistic” talking rabbits, gives new life to the concept of talking animals as acceptable subjects of serious literature. This is arguably the first example since George Orwell‘s 1945 Animal Farm.

September 1973: Lieutenant M’Ress, the feline Caitian female member of the cast in TV’s Star Trek: The Animated Series, is cited by many furry fans as one of their introductions to the concept of anthropomorphized animals for mature audiences.

November 1973: Disney’s Robin Hood animated theatrical feature with a funny-animal cast is later named by many furry fans as their earliest-remembered positive influence toward anthropomorphic animals.

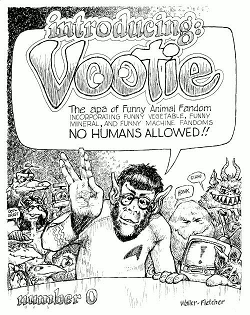

April 1976: Reed Waller and Ken Fletcher in Minneapolis start the APA Vootie, “the fanzine of the Funny Animal Liberation Front,” for cartoonists. It is more of a semi-underground comix artists’ club than open to funny-animal fans in general, but it publicizes funny-animal characters in mature settings, notably Reed Waller’s “Omaha” the Cat Dancer.

April 1976: Reed Waller and Ken Fletcher in Minneapolis start the APA Vootie, “the fanzine of the Funny Animal Liberation Front,” for cartoonists. It is more of a semi-underground comix artists’ club than open to funny-animal fans in general, but it publicizes funny-animal characters in mature settings, notably Reed Waller’s “Omaha” the Cat Dancer.May 1976 (through 1982): Neal Barrett, Jr.‘s Aldair in Albion introduces a series of four SF novels about animals who are bioengineered into parodies of man, and who fight for freedom to live their own lives. It is one of the first examples of dramatic SF genré novels for adult readers with a “funny-animal” cast.

1976-early 1980s: Marvel Comics’ Howard the Duck (January 1976 through March 1981; a supporting character in Marvel Comics since December 1973, created by Steve Gerber) and Star*Reach Productions‘ Quack! (July 1976 through issue six in December 1977), plus one- and two-issue underground comix and early independent comics such as No Ducks and Wild Animals, establish that anthropomorphic animals can be used in “literary” and dramatic stories as well as shock-value raunchy sex-and-drug satires.

December 1977: Dave Sim starts Cerebus the Aardvark, originally a parody of sword-and-sorcery comics but evolving into a complex, sophisticated literary work, with a strong furry protagonist amidst a human cast (to issue 300, March 2004).

November 1978: Martin Rosen‘s animated feature adaptation of Adams’ Watership Down impresses a wider and younger public than those who read the book. (With a special preview screening at the World Science Fiction Convention in Phoenix in September.)

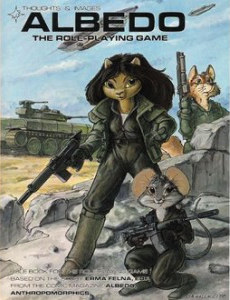

Labor Day weekend 1980: At the NorEasCon II World Science Fiction Convention in Boston (August 29–September 1), Steve Gallacci enters an Erma Felna painting in the art show, featuring a funny-animal character in a realistic high-tech military setting (later in Albedo: Anthropomorphics and Command Review). This leads to a gathering of fans to look at Gallacci’s notes for a SF comic-art serial about bioengineered animal soldiers in a space war. The discussions show a common interest in SF and fantasy about intelligent animals, such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm (fantasy), Cordwainer Smith‘s “Underpeople” stories (bioengineered animals), and H. Beam Piper‘s Little Fuzzy (animal-like intelligent aliens), to name popular examples among the three main types. This becomes an informal series of “Gallacci group” gatherings at Worldcons and Westercons to discuss anthropomorphics in SF, comic art, and animation, and to show off each others’ sketchbook art and draw in each others’ sketchbooks, from 1980 until about 1985. The group eventually splits into a club grouped around Rowrbrazzle, and the more “formal” furry parties.

May 1981: Greg Wadsworth creates Ismet, an early independent SF comic book about an oppressed funny-animal lower class rebelling against their cruel human masters (to issue five, July 1982).

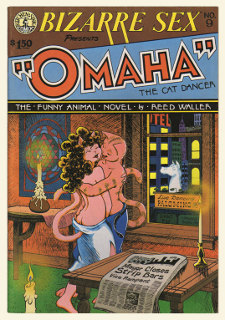

August 1981: Reed Waller’s “Omaha” the Cat Dancer, which began in the fan APA Vootie, makes its first public appearance as a book-length story in Bizarre Sex issue nine.

February 1982: Roy Thomas and Scott Shaw! launch the last major comic-book attempt at funny-animal super-heroes with DC’s Captain Carrot and His Amazing Zoo Crew (issue one in March, with a preview in The New Teen Titans issue sixteen, February 1982; to issue twenty, November 1983).

July 1982: Don Bluth‘s The Secret of NIMH animated feature (based on the 1971 juvenile novel Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, by Robert C. O’Brien) is released, depicting a hidden society of intelligent animals.

October 1982: Joshua Quagmire‘s Army Surplus Komikz Featuring Cutey Bunny is published. Cutey Bunny has continued to appear under various titles to the present.

February 1983: The final Vootie, number thirty-seven, is published as the club disintegrates through apathy.

May 1983: Alan Dean Foster‘s Spellsinger at the Gate (followed in June by Spellsinger, the mass-market edition of the first half of the story), introduces the popular Spellsinger series of funny-animal science-fantasy novels, which run for six titles through 1986 (and two more in the 1990s).

June 1983: The Tiger’s Den BBS is started by Andre Johnson in Los Angeles during 1982 as a general SF electronic bulletin board; he brings it to the “Prancing Skiltaire” in September 1983. It adds its first furry storyboard, Ken Sample‘s “The Puma’s Room”, in early 1983. By June it has enough furry participants to qualify as the first furry BBS, and by late 1983 it is almost exclusively devoted to furry storyboards. Johnson leaves the Tiger’s Den at the Prancing Skiltaire when he moves out, and it is operated by other furry fans there until it is shut down in January 1996.

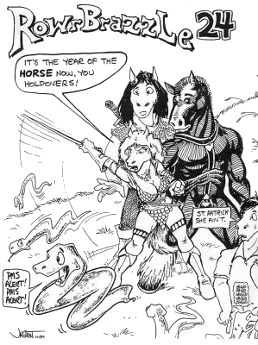

October 1983: Marc Schirmeister in Los Angeles sends out a call for fans of funny animals to join Rowrbrazzle, a new APA to replace Vootie.

October 1983: Other Suns, the first significant furry role-playing game, is published by Fantasy Games Unlimited after four years of development by creator Nicolai Shapero of Los Angeles. It includes art by Ken Sample and Fa Shimbo, and species such as Mark Merlino‘s skiltaires. Many furry fans participate in its playtesting. Other Suns sells at least twelve thousand units before FGU goes out of business.

February 1984: Rowrbrazzle number one is published. Unlike Vootie, its emphasis is more on actual funny animals than general “non-costumed-hero” comics; and it is open to anyone who can demonstrate a creative interest in funny animals, not just cartoonists (current, under new editorship; number 113 published in April 2012).

May 1984: Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird self-publish Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. It is fantastically successful, setting off a vogue for self-publishing independent comic books (including several others with anthropomorphic action-adventure heroes), and it makes funny animals respectable again to those who consider themselves too mature for “little kids’ comics”. TMNT eventually spins off television cartoons, feature films, and a separate, more juvenile series from Archie Comics, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Adventures (August 1988), which does its own bit for making “mutanimals” socially acceptable (TMNT current in various reprints and some new material; TMNTA to December 1995).

June 1984: Steve Gallacci in Seattle self-publishes Albedo: Anthropomorphics issue one under his Thoughts & Images imprint, introducing his Erma Felna of the EDF. Stan Sakai‘s Usagi Yojimbo begins in Albedo issue two, November 1984 (to March 2005, under different publishers).

This is an appropriate spot to address the Prancing Skiltaire in Orange County (south of Los Angeles) as the first furry fan commune. The Prancing Skiltaire has been Mark Merlino‘s personal fannish name for his home since before he, Rod O’Riley, Andre Johnson, and three other fans moved in September 1983 to the house at 13412 Gilbert Street, Garden Grove, California. Merlino and O’Riley have been the two permanent residents in a floating commune of (usually) four to six roomers, all fans but not all furry fans. The commune has also been active in projects in SF, comics, animé, Dr. Who, Anne McCaffrey’s Pern novels, and other fandoms. It has had a major significance in furry fandom, starting around 1984 as the center of the Tiger’s Den BBS, then furry parties and ConFurence; but to infer that the Prancing Skiltaire was created specifically to be a furry commune or that it has only been that, is incorrect.

This is an appropriate spot to address the Prancing Skiltaire in Orange County (south of Los Angeles) as the first furry fan commune. The Prancing Skiltaire has been Mark Merlino‘s personal fannish name for his home since before he, Rod O’Riley, Andre Johnson, and three other fans moved in September 1983 to the house at 13412 Gilbert Street, Garden Grove, California. Merlino and O’Riley have been the two permanent residents in a floating commune of (usually) four to six roomers, all fans but not all furry fans. The commune has also been active in projects in SF, comics, animé, Dr. Who, Anne McCaffrey’s Pern novels, and other fandoms. It has had a major significance in furry fandom, starting around 1984 as the center of the Tiger’s Den BBS, then furry parties and ConFurence; but to infer that the Prancing Skiltaire was created specifically to be a furry commune or that it has only been that, is incorrect. July 1985: Mark Merlino and Rod O’Riley host a Prancing Skiltaire party, the first publicized open funny-animal fan party, at Westercon 38 in Sacramento. It is popular enough to lead to the first furry party a year later.

July 1985: Mark Merlino and Rod O’Riley host a Prancing Skiltaire party, the first publicized open funny-animal fan party, at Westercon 38 in Sacramento. It is popular enough to lead to the first furry party a year later.July 1985: Animalympics is first screened at the Prancing Skiltaire Party. This is not the official Warner Bros. home-video release but a feature-length video compiled by Mark Merlino from the complete February 1980 half-hour TV special Animalympics: Winter Games and the WB footage for the unreleased hour-long Summer Games special edited to match it. Merlino’s video version becomes a standard feature of furry parties across America for the next decade, and is still cited by fans as one of the most influential animated furry movies.

July 1985: Jim Groat in Tucson launches his GraphXpress independent comics imprint with his and Richard Konkle’s Equine the Uncivilized (to issue seven, August 1990).

September 1985: Disney’s Adventures of the Gummi Bears, co-created and produced by Jymn Magon and Tad Stones, is the first major-studio-produced light adventure funny-animal television cartoon series to establish both popularity and longevity. (Seventy-four episodes, to September 1990; as Disney’s Gummi Bears/Winnie the Pooh Hour in its final year.) Its success leads to the popular Disney anthropomorphic adventure TV series DuckTales (Alan Zaslove and Bob Hathcock), Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers (Tad Stones and Mark Zazlov), TaleSpin (Jymn Magon and Mark Zazlov), Darkwing Duck (Tad Stones), and Gargoyles (Dennis Woodyard and others).

September 1985: Disney’s Adventures of the Gummi Bears, co-created and produced by Jymn Magon and Tad Stones, is the first major-studio-produced light adventure funny-animal television cartoon series to establish both popularity and longevity. (Seventy-four episodes, to September 1990; as Disney’s Gummi Bears/Winnie the Pooh Hour in its final year.) Its success leads to the popular Disney anthropomorphic adventure TV series DuckTales (Alan Zaslove and Bob Hathcock), Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers (Tad Stones and Mark Zazlov), TaleSpin (Jymn Magon and Mark Zazlov), Darkwing Duck (Tad Stones), and Gargoyles (Dennis Woodyard and others).November 1985: Tad Williams‘ Tailchaser’s Song is the first fantasy adventure to feature cats as intelligent characters in the manner of the rabbits in Watership Down. It helps to make anthropomorphized animals respectable for adult s-f & fantasy fans.

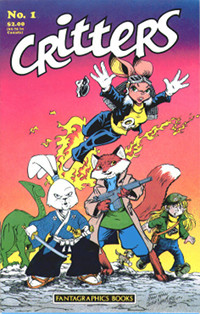

June 1986: Fantagraphics launches two particularly influential furry comics with its monthly anthology, Critters (to issue fifty, March 1990), and Mike Kazaleh‘s The Adventures of Captain Jack (to issue twelve with special issues following).

June 1986: Fantagraphics launches two particularly influential furry comics with its monthly anthology, Critters (to issue fifty, March 1990), and Mike Kazaleh‘s The Adventures of Captain Jack (to issue twelve with special issues following).July 1986: Antarctic Press‘ first furry comic is Ben Dunn‘s first Mighty Tiny short story, in Mangazine issue three. Antarctic, in San Antonio, becomes one of the major publishers of anthropomorphic comics in the early 1990s.

July 1986: After about a year of holding informal open parties at SF and comics conventions, Mark Merlino and Rod O’Riley hold the first “official” Furry Party at Westercon 39 in San Diego. This starts the tradition of publicizing the presence of ‘morph fans at conventions by posting “furry party” flyers featuring funny-animal pin-up art. The furry party name leads to the characterization of these fans as “furry fandom” by the late 1980s.

August 1986: As a result of a ban in Rowrbrazzle of explicit sexual material, Jim Price in Atlanta starts Q, “the Mature Funny-Animal APA”. (Through issue ten, 1989.)

August 1986: Lee Marrs‘ Pre-Teen Dirty-Gene Kung-Fu Kangaroos #1 is one of the best of the TMNT-inspired rip-offs of the late ‘80s; typically with a ridiculous title and a short run. To #3, January 1987. Others included Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters #1, January (?)1986 – #9, January 1988, by Don Chin, Patrick Parsons (Parsonavich) and Sam Keith); Geriatric Gangrene Jujitsu Gerbils #1, January 1986 – #3,?, by Tony Basilicato; Cold Blooded Chameleon Commandos #1, August 1986 – #5, June 1987, by William Clausen & Michael Kelley; Mildly-Microwaved Pre-Pubescent Gophers, July 1986 (one-shot, no credits); Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas, October 1986 (one-shot, by Sean Deming, Gerald Forton, and Danny Green); and at least a half-dozen more. There were also, following the success of the TV cartoons, unauthorized imitations of the TMNT in other TV cartoons, movies, video and RPG games, and action figures.

October 1986: “Omaha” the Cat Dancer issue three begins the regular publication of Reed Waller‘s influential and critically acclaimed mature soap-opera serial, after Kate Worley becomes its regular writer, after sporadic underground short stories in 1983 and two issues of its own title in 1984 and early 1986 (to issue 24, February 1995;

uncompleted storyline published after Kate Worley’s death, 2005 to 2007).

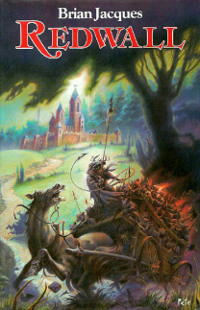

uncompleted storyline published after Kate Worley’s death, 2005 to 2007).November 1986: Redwall, the first novel in Brian Jacques‘ longrunning British series about the peaceful animal abbey, run by mostly small herbivores and omnivores such as mice and squirrels, in the forested land of Mossflower which is constantly being invaded by villainous carnivores, is published (June 1987 in America). Marketed as children’s books in Britain and as adult fantasy novels in America, the series is exceedingly popular in Europe and America, and helps to promote anthropomorphic literature for all ages. There are 22 novels in the series, ending with Jacques’ death in 2011; plus a 1999–2003 animated TV series by Nelvana of Toronto and comic book adaptations of the first three novels.

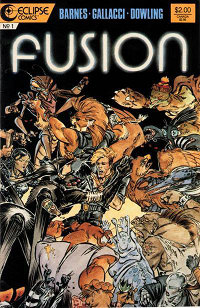

January 1987: Fusion (Eclipse Comics) introduces the SF comic book adventures of the Tsunami, a tramp spaceship with a mixed crew of humans, bioengineered animals, and furry aliens (by Lex Nakashima, Steve Gallacci, Lela Dowling, and others);

with the humorous back-up series The Weasel Patrol, by Nakashima, Dowling, and Ken Macklin (to issue #17, October 1989).

with the humorous back-up series The Weasel Patrol, by Nakashima, Dowling, and Ken Macklin (to issue #17, October 1989).April 1987: Jim Groat begins Morphs as the first anthology comic for ‘morphic beginning writers and artists (to issue four, September 1988).

April 1987: Ed Zolna in Roslyn, PA creates Mailbox Books, originally only to sell his Fran an’ Maabl self-published comic book. It quickly becomes furry fandom’s first comprehensive mail-order book service, attempting to stock just about every furry book, comic book, art folio, and fanzine that is published (to April 1999, when Zolna sells the stock to Sean Rabbitt of Las Vegas, NV, who merges it with his older Rabbit Valley Books in October 2001).

May 1987: Mark Merlino and the furry party crew encourage the “adoption” of the annual Baycon SF convention in San Jose, California over the Memorial Day weekend as the convention for furry fans to congregate at. There are large furry attendances at this and the next two or three Baycons, but active hostility by non-furry fans eventually causes problems.

May 1987: Kyim Granger (Karl Maurer) in Oakland starts Furversion as the newsletter of the furry party crowd. It quickly evolves into furry fandom’s first independent fiction and art magazine (to issue twenty-one, Nov. 1990).

May 1987: The Electric Holt is started by Richard Chandler (sysop), Mitch Marmel (assistant sysop), John DeWeese, and Seth Grenald at Drexel University in Philadelphia. It is the first east coast BBS with an extensive furry users’ group, thanks to Chandler and Marmel.

(It also features ElfQuest, animé, and general SF storyboards.) It lasts until 1990, when the four graduate from Drexel.

(It also features ElfQuest, animé, and general SF storyboards.) It lasts until 1990, when the four graduate from Drexel.August 1987: Mark Merlino and the furry party crew host a furry party at Conspiracy ’87, the 1987 World Science Fiction Convention in Brighton (August 27–September 2). This is the first furry event in Britain. Early British furry fans credit this party with introducing them to American furry independent comic books and fanzines, which eventually leads to a British furry fandom around 1992–1993.

September 1987: Ralph Bakshi‘s and John Kricfalusi‘s Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures establishes television-cartoon funny animals as respectable for “adult” viewers. (Thirty-seven episodes, to August 1989.) November 1987: Amazing Heroes issue 129 (Fantagraphics) is a special funny animal issue highlighting independent furry comics, Rowrbrazzle, and the Bakshi/Kricfalusi TV cartoon series, Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures. Numerous furry fans later say they first learned about furry fandom from this issue.

November 1987: Amazing Heroes issue 129 (Fantagraphics) is a special funny animal issue highlighting independent furry comics, Rowrbrazzle, and the Bakshi/Kricfalusi TV cartoon series, Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures. Numerous furry fans later say they first learned about furry fandom from this issue.

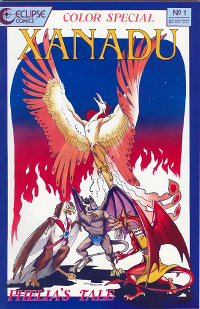

May 1988: Vicky Wyman’s Xanadu (Thoughts & Images) introduces furry swashbuckling romantic fantasy. It continues to today, both as an irregular independent comic book (different publishers, to MU Press’ Xanadu: Across Diamond Seas issue 5, May 1994) and through its fanzine, The Ever-Changing Palace.

June 1988: Mary Stanton‘s The Heavenly Horse from the Outermost West, followed by Piper at the Gate the next year, introduces the Army of One Hundred and Five (recognized breeds of horses), and does for horses what Watership Down and Tailchaser’s Song did for rabbits and cats.

January 1989: ConFurence Zero, the first exclusively furry convention, is held 21–22 January at the Holiday Inn Bristol Plaza in Costa Mesa, California, organized by Mark Merlino, Rod O’Riley, and others. (“Zero” because it is considered a test for a ‘real’ furry convention the next year.) Membership is about 90, attendance is 65, including most prominent furry fans from across North America and Steve Kerry from Australia. Art Show auction sales are over $1,100, including $450 for a Susan Van Camp painting. One programming track is on “Furry Costuming”.

May 1989: Martin Wagner self-publishes Hepcats, turning his earlier college-newspaper humorous comic-strip into a critically acclaimed furry human-interest serial involving mature themes such as child abuse and suicide (new series from Antarctic Press, to issue 12, June 1998).

July 1989: MU Press‘ first anthropomorphic comic book is Steve Willis‘ Morty the Dog issue one, a collection of Willis’ strips from small-press and mini-comics of the early eighties. MU Press, in Seattle, becomes one of the major publishers of anthropomorphic comics in the early 1990s. August 1989: FURtherance, published by Runé (Ray Rooney) in Philadelphia, is the first of several new fanzines, mostly short-lived, devoted to furry literature and art (to issue three, winter 1991).

August 1989: FURtherance, published by Runé (Ray Rooney) in Philadelphia, is the first of several new fanzines, mostly short-lived, devoted to furry literature and art (to issue three, winter 1991).

August 1989: FurNet is started by Nicolai Shapero as a network (through FidoNet) of BBSs with furry discussion areas. By 1996 it includes over twenty furry BBSs throughout North America.

November 1989: Robert and Brenda Daverin in the San Francisco Bay area start FurNography, one of the first public fanzine-art folios for furry eroticism (to #4, June 1991).

November 1989: Richard Chandler in Philadelphia starts Gallery as a cross between an artists’ and writers’ APA and a commercial magazine for general furry fans (to issue 50, Winter 2004).

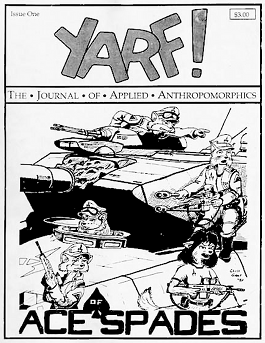

January 1990: ConFurence 1, the “first real” furry convention, is held 26–28 January, again at the Holiday Inn Bristol Plaza in Costa Mesa, California. Membership is 145; attendance is 130. The ConFurence adds guests of honor (Jim Groat, Monika Livingston, Martin Wagner) and awards (Best Costume, to John Cawley as Zorro the Fox; Art Show Best of Show, to Ken Sample‘s “Winter Charge”; Best Filk Award, to Kay Shapero‘s “Furry”). January 1990: Yarf! is begun by Jeff Ferris, Kris Kreutzman, and others in the San Francisco Bay Area to replace the moribund Furversion. Debuting at ConFurence 1, it becomes furry fandom’s most reliable general magazine (to issue 69, September 2003).

January 1990: Yarf! is begun by Jeff Ferris, Kris Kreutzman, and others in the San Francisco Bay Area to replace the moribund Furversion. Debuting at ConFurence 1, it becomes furry fandom’s most reliable general magazine (to issue 69, September 2003).

March 1990: MU Press’ first original anthropomorphic title is Dwight R. Decker’s and Teri S. Wood’s Rhudiprrt, Prince of Fur issue one. (to issue 12, May 2004; Will Faust replaced Wood as the artist)

Spring 1990: Mythagoras, an excellent literary furry fanzine, is published by Bill Biersdorf and Watts Martin in Tampa (to issue three, Autumn 1990).

September 1990: The Furry Home at Squirrel Hill (2613 Tilbury Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) is started as a furry commune by Centaur (Paul Blair), Ashtoreth (William Haas), Drew Maxwell, and Shaterri (Steve Stadnicki). All are students at or work at Carnegie-Mellon University, and all had been role-playing furry characters on a general SF multi-user dimension, Islandia, until it shut down that summer. The Home lasts as a furry commune through several student generations until around 1994, when the last furry fans are replaced by non-fannish students.

September 1990: Meet the Feebles, a December 1989 New Zealand feature film directed by Peter Jackson, is shown at the Toronto International Film Festival. It becomes famous throughout furry fandom as a hilariously raunchy parody of The Muppet Show starring foul-mouthed and degenerate anthropomorphic-animal hand puppets such as Heidi (hippopotamus), Bletch (walrus), Samantha (cat), and Trevor (rat). The film is not distributed in the U.S. until September 1995, following which bootleg videos and later legitimate video and DVD releases from 1998 become widespread.

September 1990: (Steven Spielberg presents) Tiny Toon Adventures, created and directed by Tom Ruegger, is co-produced by Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment and the re-formed Warner Bros. Animation studio. The cast featuring juvenile counterparts of Warner Bros. cartoon stars, including Buster and Babs Bunny, Plucky Duck, Hamton J. Pig, Fifi La Fume, Dizzy Devil, and others become favorites with furry fans. They also inspire considerable furry-fan pornography, which becomes so extensive that it results in a story in The Hollywood Reporter (November 1, 1995) and a chapter, “Fans versus Time Warner: Who Owns Looney Tunes?” by Bill Mikulak, in the book Reading the Rabbit: Explorations in Warner Bros. Animation, edited by Kevin S. Sandler (June 1998). It includes 98 episodes in three seasons to December 1992, plus a direct-to-video feature, Tiny Toon Adventures: How I Spent My Vacation (March 1992) and two TV specials in 1994 and 1995.

November 1990: FurryMUCK is built as the first exclusively Furry MU* by the denizens of the Furry Home at Squirrel Hill plus Claire Benedikt, with Drew Maxwell as the prime wizard, to replace the defunct Islandia. By 1996 it has more than two thousand users worldwide, with two hundred to three hundred log-ons per evening. The core group shifts around late 1992–early 1993 from Pittsburgh to the Bay Area, as the wizards graduate from Carnegie-Mellon and settle into the Silicon Valley computer industry.

November 1990: The first furry Usenet newsgroup, alt.fan.furry, is started by Peter da Silva in Houston as alt.fan.albedo. He changes the name to alt.fan.furry two months later to make it more generic.

December 1990: Gary Sutton in Poulsbo, a suburb of Seattle, starts the Furry Press Network as furry fandom’s second major APA. Despite a successful start, Sutton kills it in early 1992 by refusing to allow its other members to continue it after he gives it up.

January 1991: ConFurence 2, on 25–27 January at the Holiday Inn, Anaheim, California, grows to an attendance of more than 200. Guests of Honor are Reed Waller, Kate Worley, Steve Gallacci, and Vicky Wyman. It is the first to have attendees from mundane companies (Carl Gafford and Len Wein of Disney Comics). The art show auction brings in over $3,000.

March 1991: The Tai-Pan Project, featuring stories set on a furry-crewed tramp spaceship, is started as a shared-world writers’ project edited by a group of Seattle fans chaired by Whitney Ware (current, under new editorship and title, Tales of the Tai-Pan Universe).

June 1991: Mark Merlino and the ConFurence group publish a fanzine, Touch (to issue three, August 1992).

July 1991: The Furkindred: A Shared World is started by Charles Melville and Edd Vick at MU Press as a writers’ and artists’ project. Stories adhere to guidelines describing a furry world, its nations and politics (to issue 3 and a graphic novel, The Furkindred: Let Sleeping Gods Lie, February 1997).

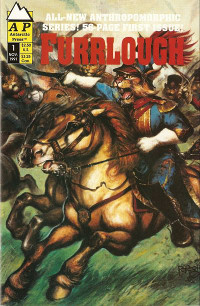

November 1991: Antarctic Press begins Furrlough, a monthly anthology comic book for furry action-adventure stories (transferred to Radio Comix with issue 52, April 1997; to issue 191, November 2011).

February 1992: The “First British Furry Micro-Con” is held 1–2 February, when Ian Curtis invites furry fans throughout Britain (only about a dozen) to meet a group of visiting American fans. A dozen fans (six American and six English) spend the weekend partying at Curtis’ home in the village of Yateley, Surrey, England.

February 1992: Dwight J. Dutton in Huntington Beach, California turns Huzzah! (previously an Albedo fanzine) into an invitational furry artists’ APA starting with its issue four (to issue 50, January 2004).

May 1992: Shanda the Panda, created and written by Mike Curtis in Beaumont, Texas (later Conway, Arkansas), debuts from MU Press. By the end of 1996, Shanda holds a record for the number of publishers (MU, Antarctic, Vision Comics, and Curtis’ own Shanda Fantasy Arts) and artists who have produced her adventures.

July 1992: Growl (Paul Groulx) in Frankford, Ontario starts the FURthest North Crew as an APA for primarily Canadian furry fans. It is almost immediately filled by former Furry Press Network members, and becomes furry fandom’s third strong APA (current, under new editorship).

August 1992: Mortality comes to furry fandom when popular fan artist Charles “Deal” Whitley of New Haven, Connecticut succumbs after a lifelong struggle against sickle-cell anemia, on 30 August.

January 1993: Robert C. King coins the term “fursuit” for the Fursuit Mailing List, for full-body anthropomorphic animal costumes worn at furry conventions.

June 1993: Jan Paxton invites furry fans around Britain to a weekend party at his parents’ home in Tonyrefail, South Wales, 5–7 June. About ten fans attend.

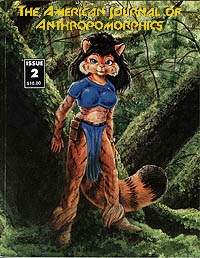

June 1993: Antarctic Press starts Genus as an anthology comic book for furry mature erotic humor (transferred to Radio Comix with issue 23, April 1997, to issue 93, February 2011). September 1993: Darrell Benvenuto in New York starts The American Journal of Anthropomorphics, an annual coffee-table-format collection of furry art (to issue four, 1997).

September 1993: Darrell Benvenuto in New York starts The American Journal of Anthropomorphics, an annual coffee-table-format collection of furry art (to issue four, 1997).

September 1993: Biker Mice from Mars begins a three-season broadcast, to episode #28, February 1996. This is the best and most popular of the imitation-TMNT TV cartoons, with its own three-issue comic book, video games in 1994 and 2006, and an August 2006 revival with 28 new TV episodes, to July 2007.

September 1993: Tiny Toon Adventures leads directly to the even more popular (Steven Spielberg presents) Animaniacs, also created by Tom Ruegger, and starring Wakko, Yakko, and Dot, the three what-are-they? anthropomorphic animal WB siblings who live inside the water tower on the WB studio lot. Although the series features several other cartoon animal characters including Slappy Squirrel and her nephew Skippy, and the mice Pinky and the Brain, the fan favorite is clearly ultra-sexy Minerva Mink, who is drafted as the fan-fiction femme fatale of several furry conventions. The program lasts for 99 episodes through November 1998, plus a theatrical short, “I’m Mad“, in March 1994, and a direct-to-video feature, Wakko’s Wish, in December 1999. September 1993: SWAT Kats: The Radical Squadron is a Hanna-Barbera animated TV series that comes the closest to costumed-hero action-adventure cartoons with a furry cast. Set in Megakat City, Chance “T-Bone” Furlong and Jake “Razor” Clawson are unfairly cashiered from the semi-military Enforcers and assigned as mechanics in the city’s salvage yard. Secretly building their own Turbokat jet fighter, they fight supervillains and other menaces as masked heroes, earning the cat citizens’ gratitude but dismissed and hunted by proud Commander Ulysses Feral and his Enforcers (who are jealous of them as rivals) as recklessly dangerous vigilantes. 25 episodes are broadcast (to January 1995) and it is the most popular syndicated TV cartoon series of 1994, but its abrupt cancellation (with three episodes still in production) and a lack of merchandising items leaves fans frustrated.

September 1993: SWAT Kats: The Radical Squadron is a Hanna-Barbera animated TV series that comes the closest to costumed-hero action-adventure cartoons with a furry cast. Set in Megakat City, Chance “T-Bone” Furlong and Jake “Razor” Clawson are unfairly cashiered from the semi-military Enforcers and assigned as mechanics in the city’s salvage yard. Secretly building their own Turbokat jet fighter, they fight supervillains and other menaces as masked heroes, earning the cat citizens’ gratitude but dismissed and hunted by proud Commander Ulysses Feral and his Enforcers (who are jealous of them as rivals) as recklessly dangerous vigilantes. 25 episodes are broadcast (to January 1995) and it is the most popular syndicated TV cartoon series of 1994, but its abrupt cancellation (with three episodes still in production) and a lack of merchandising items leaves fans frustrated.

October 1993: Damian Cugley (Slate) in Oxford publishes the first British furry fanzine, Furry Furry issue one, autumn/winter 1993. (To issue two, spring/summer [May] 1994.)

December 1993: Anthropomorphine, the first successful British furry fanzine, is published by Kevin Charlesworth of Hailsham, East Sussex (transferred to Lazy Fox Studios, to issue 14, June 2010).

January 1994: After “rattling around” with attendances in the low hundreds at different hotels, ConFurence V almost fills the Airporter Garden Hotel in Irvine, California, 21–23 January, with an attendance of slightly more than six hundred. The Airporter, with its friendly management, becomes the first real “home” for ConFurence. A Rowrbrazzle tenth anniversary celebration is held.

April 1994: Ian Curtis hosts another weekend furry party at his home in Yateley, 22–24 April. This is called Furry Housecon 3, retroactively assigning #1 and #2 to his February 1992 party and Jan Paxton’s June 1993 party. Furry Housecons have been hosted by Curtis in Yateley approximately quarterly since then (#13, 29 November–1 December 1996; attendance sixteen UK fans and two German fans). The average attendance is around fifteen.

July 1994: The first annual UK Fur CON is held 9–11 July, organized through FurryMUCK by Adam Moss as an informal house party at his home in Colchester, Essex. About fifteen fans attend, including one each from Germany and the U.S. Furry Housecon 4 is the same weekend (8–10 July), and accusations of “trying to hijack our con” against the Housecon are later put down to an innocent lack of communication between Britain’s FurryMUCK and non-Internet furry fans. The two series of house parties are mutually coordinated today.

Winter 1994: PawPrints Fanzine, one of the highest-quality literary/art furry fanzines, is started by Conrad Wong (Lynx) and T. Jordan Peacock (Greywolf) of Los Altos, California (to issue 12, Fall 2001).

November 1994: Martin Dudman in Keston, a suburb of London, launches the first major British furry fanzine, the quarterly Fur Scene: The Anthropomorphic Newsletter (to issue 11, February 1998). Dudman also starts United Publications, a mail-order service to import American furry books, comics, and fanzines for British fans, and vice versa.

November 1994: As a result of perceived anti-furry prejudice at the annual Philcon SF convention in Philadelphia, east coast furry fans hold their own Furtasticon I. (Some furry fans are declined space in Philcon’s art show or dealers’ room when their applications arrive after both are all booked up.) Furtasticon is organized by Trish Ny of Cleveland at the Holiday Inn City Line in Philadelphia, 18–20 November. Organized on a couple of months’ notice, it draws about 230 fans from across North America and creates a demand for an annual furry convention for eastern North America

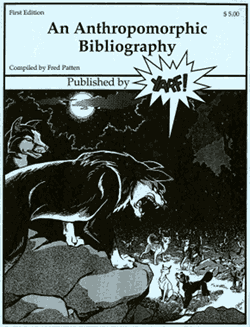

January 1995: An Anthropomorphic Bibliography, by Fred Patten in Los Angeles, is published by Yarf! as the first bibliographic compilation of general literature and SF genré novels featuring anthropomorphized animals. Its unexpected popularity leads to an expanded second edition in August 1996, and a third edition [cover] in January 2000. April 1995: Paul Kidd‘s Mus of Kerbridge, by a popular furry fan, is considered by furry fans as a novel by “one of us” and proof that furry-authored fiction can sell to the mainstream fantasy market.

April 1995: Paul Kidd‘s Mus of Kerbridge, by a popular furry fan, is considered by furry fans as a novel by “one of us” and proof that furry-authored fiction can sell to the mainstream fantasy market.

May 1995: UK Fur CON 2 is held 26–30 May, organized by Ian Stradling at his home in Bristol. About twenty show up to his house party, including a fan from Germany. Videos shown include the British premiere of Eric Schwartz‘s furry animation.

June 1995: EuroFurence 1 is held 30 June–3 July; organized over the Internet by Gerritt Heitsch and Tobias Köhler as a house party at Heitsch’s parents’ vacation farm in Kaiser Wilhelm Koog (near Hamburg), Germany. Nineteen attend from Northern Europe and Britain. Activities include watching furry videos and drawing in each others’ sketchbooks.

July 1995: South Fur Lands is started by Jason Gaffney in Brisbane as the first major Australasian furry fanzine. It is continued from issue 20, March 2001, by Bernard Doove in Melbourne (to issue 57, December 2011).

September 1995: Ian Curtis hosts a “British Furry Convention” (Furry Housecon 8) at his home in Yateley 1–4 September, so British fans can meet American fans visiting England after the 1995 World Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow the previous week. About twenty American and British fans gather to party and to take the American fans on a furry tour of London and Oxford.

September 1995: Newspaper cartoonist Bill Holbrook‘s Kevin & Kell, about a rabbit’s and wolf’s controversial predator-prey mixed marriage in the city of Domain in a totally anthropomorphized world, begins on 3 September as the Internet’s first original daily comic strip. The success of Kevin & Kell leads to hundreds of daily, semi-weekly, weekly, monthly, and sporadic original online comic strips today (current).

October 1995: Furtasticon evolves into ConFurence East, held at the Holiday Inn Jetport in Elizabeth, New Jersey, 13–15 October. It is organized by Trish Ny and her family. Guests of Honor are Vicky Wyman, S. Andrew Swann, and E.L.V.I.S. Convention Services. Attendance is 449.  The program more resembles a traditional SF convention format with many panels than the more informal ConFurence. The art show includes 795 pieces of art; sales are near $11,000. An official charity is heavily promoted: Wolf Park nature study preserve at Battle Ground, Indiana. The Sci-Fi Channel covers the convention.

The program more resembles a traditional SF convention format with many panels than the more informal ConFurence. The art show includes 795 pieces of art; sales are near $11,000. An official charity is heavily promoted: Wolf Park nature study preserve at Battle Ground, Indiana. The Sci-Fi Channel covers the convention.

January 1996: ConFurence VII, 12–14 January, spills over into both Irvine, California’s Airporter Garden (renamed Atrium Marquis) Hotel and the next-door Radisson Plaza Hotel, with a membership of 999 and attendance of 875. Many fans arrive on the eleventh to make it an informal four-day convention. The convention awards its first Golden Sydney Award (statuette by Ruben Avila), “to a person in ‘mainstream’ media or publishing who has helped to create a more ‘furry friendly’ atmosphere for anthropomorphic material and fandom”; the first recipient is Disney animation writer-director Jymn Magon (TaleSpin, A Goofy Movie, et cetera). Art Show sales reach almost $30,000. There is general agreement that, as popular as the Airporter Hotel has been, ConFurence needs a larger venue.

January 1996: Mike and Carole Curtis in Conway, Arkansas turn their Shanda Fantasy Arts small-press art folios into a full comic-book imprint with the Giant Shanda Animal (annual) at ConFurence VII. The imprint becomes a regular anthropomorphic comic publisher starting with the release of Katmandu: Velites and Hoplites and New Horizons issue one at ConFurence East 1996 in November.

April 1996: Quarantine (9 Kitching Street, Chapel Hill [Brisbane], Queensland), is started by Chris Baird, Jason Gaffney, Marko Laine, and Simon Raboczi as the first Australian furry commune. It is the publication office of South Fur Lands (edited by Gaffney), and the Net center for OzFurry (moderated by Baird).

May 1996: Darrell Benvenuto launches Vision Comics as a major specialty furry comics line, with four bimonthly titles — Kjartan Arnörsson‘s Savage Funnies, Mark Shaw’s The Hollow Earth (both new), Carole Curtis‘ Katmandu, and Mike Curtis‘ Shanda the Panda (both from Antarctic Press) — and announced plans for others.

June 1996: UK Fur CON 3 is held 14–16 June, organized by Kevin Charlesworth as a party at his student house in Coventry. About fifteen attend. The main events are games of laserquest and soccer.

July 1996: EuroFurence 2 is held 18–22 July in Linköping, Sweden, organized by Snout (Henrik Isacsson) in a rented school building. About thirty fans from Sweden, Finland, Britain, and Germany attend, mostly Internet Eurofurries meeting in person. There are furry hall costumes, a martial arts demonstration, sketching, and a zoo trip. Chama (Thomas Hagenfeldt) premieres a EuroFurence Hymn.

Labor Day weekend 1996: At the L.A.con III World Science Fiction Convention in Anaheim, south of Los Angeles (August 29–Sept. 2), a Furry Fandom Lounge operated by the ConFurence committee becomes essentially a five-day furry convention within the Worldcon. Its panels, demonstrations, and evening furry parties are integrated into and publicized within the general Worldcon program schedule. A glass-showcased History of Furry Fandom exhibit assembled by David Bliss is included among the Worldcon’s exhibitions. A general SF trivia quiz includes a block of “Fins, Feathers, and Furry” questions.

October 1996: The New York Times Magazine, 27 October, has a brief article (pg. 25) about “a growing subculture of furry-suit hobbyists who don pelts, whiskers and tails year-round. They hold conventions — ‘conFURences’ — and use the Internet to swap stories about the fun of role-playing as otters, foxes, and beavers.”

November 1996: ConFurence East 1996, 15–17 November, moves to the Holiday Inn Independence in Cleveland, Ohio. Guests of Honor are Susan Van Camp, Paul Kidd, White Wolf Game Studios, and White Wolf artist Andrew Bates. Attendance is estimated at around five hundred. The dealers’ room of fifty tables is sold out. The art show has fewer entries (596 pieces), but greater sales ($12,400). Many attendees carpool to a local theater for the premiere of Warner Bros.’ Space Jam that weekend. Trish Ny announces that this hotel will remain the convention’s venue for the next several years, and that the convention’s name will change to MoreFurCon to avoid confusion with the established ConFurence. A third annual furry convention, Albany Anthrocon, to be held in Albany, New York over the Fourth of July weekend starting in 1997, is announced.

Author’s note: Many fans helped supply the information for this chronology, and we thank all of them. Special thanks go to Simon Barber, Richard Chandler, Ian Curtis, Martin Dudman, William Fortier, Mark Merlino, Rod O’Riley, Nicolai Shapero, Steve Stadnicki, and Ian Stradling, who not only went to considerable trouble to dig through old records to find some exact dates, but who helped to get information from other fans to make this chronology as accurate as possible.

Editor’s note: Flayrah has provided links to additional information within this piece. Unless indicated, these links are not the source of the information provided here. Frequently, the reverse is true; they rely in part on an earlier version of this document.

This is just fantastic. Thank you!!

This brings back memories. Foster’s Spellsinger books sure did make an impression on me when I was 12 or so, in 1990. I can’t imagine I would find them of very high literary merit today, I would probably find them clumsy and pulpy, but I still have great memories (such is the nostalgia lens.) It’s cool how certain books have that kind of power at a certain age, and there’s nothing wrong with writing like that.

It’s amazing that there was a furry BBS in 1983!

One thing that strikes me is how dedicated fans were to putting fan culture in print, at the time, with the independent comic boom of the 80’s. It reminds me of hunting down zines and doing lots of mail ordering, pen pal mailing, and tape trading during the 90’s boom in DIY zines. I’m a little sad that a lot of it has faded behind the internet’s easier to access, but more ephemeral things. (This blog is a great resource though.) Webcomics are certainly widely read and nicely made, but I don’t feel the same energy from them (I don’t read any). I dislike gaming/second life/etc for being walled-in.

That comes with awareness that “furry” isn’t centered on a brand owned by Disney or a large corporation, and that’s great. Looking at this list, many things look like they cross over pop culture and fan culture in a more potent way than today, when things are published to the internet and its’ static noise. The 80’s independent comic boom made it possible for something like TMNT to become it’s own huge property that was started by indie artists. How possible is that today?

I could be wrong about those qualities of “furry fan media”, but these days I feel like live events is where the most energy is. (Living in the SF bay area is making me feel like that.) I think the quality of fursuits and amount of suiters you can see in one place is evidence of that.

Well, that was informative.

Well, I’ll be…

Wow, I really enjoyed reading through all of that! It’s really interesting to note the history of the furry fandom and what has inspired its members! I loved reading this article and will there possibly be a continuation, documenting significant furry events after 1996 as well?

Right now, a continuation of the chronology after 1996 looks doubtful. This chronology was written in 1996, documenting the events while they were fresh. After 1996, there were both too many events (the furry conventions around North America proliferated; furry events started in other countries; there were more influential events from outside of the fandom such as the Vanity Fair article and the CSI episode), and the events would be documented from much longer ago. But it is certainly a worthwhile long-term goal. As I said in the introduction, a detailed history of furry fandom is yet to be written.

Fred Patten

Sure. It’s called WikiFur. Try starting here. You can even help out! 🙂

But seriously . . . if you wanted to pull the whole thing together, it’d take a book, and not a short one. Something like Sam Mokowitz‘s Immortal Storm, or Harry Warner, Jr.‘s All Our Yesterdays and A Wealth of Fable. Judging by these, it takes a couple of decades to gain sufficient historical perspective on events — or perhaps just to let the flames die down . . .

It would be cool to have a more formal published history of furry fandom, but it would also be a huge project. Maybe splitting it into chapters and giving them to those with most knowledge of individual topics might make it more manageable.

Yes; well, to repeat something that I wrote four years ago for Rowrbrazzle …

There is one project that I have abandoned: writing Animal Masks, the “real book” history of furry fandom. Joe Strike asked at the beginning of January if I would object if he wrote such a book, if I was not going to. Not at all. Since someone asks me every couple of years what happened to my history, here is the sad story.

My Animal Masks book never really got started. Mike Curtis at Shanda Fantasy Arts got the idea for the book in 1997 and asked me to write it. I was enthusiastic about writing a Furry Fandom equivalent of the histories of s-f fandom like Sam Moskowitz’s The Immortal Storm and Harry Warner Jr.’s All Our Yesterdays, and I agreed to write it. I also told him that Moskowitz’s and Warner’s books had each taken ten years to write, and that I would try to finish mine sooner than that but it would still probably take at least five years to do all the in-depth research, interview furry fans throughout the world by correspondence, get photographs & other illustrations, etc. Curtis promptly sent out press releases announcing that the book would be published in two years:

Coming in 1999:

Animal Masks: Anthropomorphics As Modern Totems, the first history of our field, written by Fred Patten.

This is from a ConFurence 9 (January 1998) convention report by Watts Martin:

The History of Furry Fandom panel was also interesting, although it was mostly stuff I already knew. Its host was Fred Patten, who’s putting together a book for publication next year called Animal Masks that will be a fifteen-year history of the fandom, apparently a coffee-table compendium useful both to give older fans a clear idea of where the fandom actually came from and to be an introduction to new fans. This is a welcome idea; some of the complaints batted about relating to fan behavior, online and off, trace back to people having very little idea what furrydom really is. The very small number who are ongoing problems seem to take a perverse pride in having no interest in the fandom’s history, though–but I suppose the book really isn’t aimed at fuggheads. It was also nice to see Mark Merlino at the panel looking relatively relaxed, a state I don’t think I’ve seen him in for years.

This is a letter that I wrote published in Mike Glyer’s File 770 #127, November 1998, when I had just stopped giving the project top priority but still planned to write it eventually:

The Fur Frontier

Fred Patten agrees, “Yes, I am writing a history of furry fandom, and Joe Rosales is also planning a ‘Brian Aldiss’ history of furry/talking animals in popular culture.” But he feels that Taral’s comments about these projects, quoted in File 770:125, while accurate in general are erroneous in detail. Neither Patten nor Rosales feel their books are “revisionist” views of the same topic, any more than one would claim that Aldiss’ The Billion-Year Spree is a revisionist view of Harry Warner’s All Our Yesterdays. Rosales will focus on literature and popular culture, and Patten will chronicle furry fandom.

Patten will only supply a broad overview of the history before moving on to his main topic, furry fandom:

There is an Egyptian tomb painting ca. 1500 B.C. of a lion and a gazelle playing whatever the Egyptian equivalent of checkers was. This is a bit more indisputably ‘funny animal’ than animal-headed gods, or neolithic cave paintings of what might have been anthropomorphized animals but could equally well have been tribal shamans dressed in animal skins. Parables featuring talking animals can be traced from the tales of Aesop and Terence through the Medieval ballads of Reynard the Fox to the refined literary fantasies of the 18th century French Court and the ‘Uncle Remus’ Afro-American folk tales of the 19th century. (And don’t forget the Monkey King tales in the Orient.)

Anthropomorphics have especially proliferated during the most recent 200 years, with the popularization of talking animals in children’s’ literature (Lewis Carroll, etc.); talking animals in political cartoons (which predate Thomas Nast’s Democratic donkey and Republican elephant); advertising mascots like Tony the Tiger and the Trix rabbit; movie and newspaper funny-animal stars like Krazy Kat, Mickey Mouse and Pogo Possum; and so on. I will summarize all this in a very broad overview as the Introduction to my history of organized furry fandom. Rosales will concentrate entirely on the history of talking animals through 5,000 years or more of popular culture.

My thesis is that furry fandom coalesced out of sf fandom and comics fandom, blending elements from both of them and achieving its own critical mass in 1983/1984. The first clear signs of the independent furry fandom were the creation of its first apa, Rowrbrazzle, and the decision by some fans to self-publish furry comic books because there seemed to be enough fans of stories with talking animals to support them (as distinct from earlier attempts to self-publish comics which had to hope for sufficient sales from the general public alone.) Some key titles in this evolution of ‘furrydom’ were Cutey Bunny (which first appeared in October 1982 but attracted attention during 1983), Alan Dean Foster’s Spellsinger novels starting in mid-’83 (influential in establishing funny animals as respectable reading for adults), and the Rowrbrazzle apa and the comics Albedo, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Usagi Yojimbo all during 1984. Critters and Captain Jack weren’t until 1986.

Rowrbrazzle started in February 1984. Since it was specifically an apa for writing and drawing funny animals as a genre and discussing the new fandom that was forming about them, it is a handy landmark to say that ‘furry fandom existed at this time.’ I do not claim, as Taral implies, that furry fandom was started by the birth of Rowrbrazzle. But I have asked whether anyone can supply an earlier date that can be clearly identified as belonging to furry fandom, as distinct from being an isolated furry event within sf fandom (such as the preview of the Watership Down movie at the 1978 Worldcon) or comics fandom (such as R. Crumb’s Fritz the Cat in 1968 or Marvel Comics Howard the Duck in 1976); and so far nobody has.

Considering that the worthwhile histories of fandom such as Sam Moskowitz’s The Immortal Storm and Harry Warner’s All Our Yesterdays and A Wealth of Fable have each taken about a decade to write, I will be very surprised if my book (working title: Animal Masks) is ready for publication as soon as next year.

In 2001 Edd Vick offered to publish it as a MU Press book if I ever finished it, but by then I considered the project dead for the reasons given in this unpublished interview:

Interviewer: You mentioned a history of furry fandom in the book [Best in Show]. Can you tell us about it?

Fred: Since it was in the Afterword, it was of necessity only a very brief summary. In fact at one time around 1998, Mike Curtis of Shanda Fantasy Arts wanted me to write a complete book–length history of Furry fandom, to be titled Animal Masks. I said I would do so, but it never got done for two main reasons. In the first place, I told Curtis it would probably take about five to ten years to do, assuming that it would take about as long as the histories of science fiction fandom that were done. Sam Moskowitz’ The Immortal Storm, his history of science fiction fandom in the 1930s, and Harry Warner Jr.’s All Our Yesterdays, his history of fandom in the ‘40s, both took between five to ten years to write. But Shanda Fantasy Arts wanted to publish it right away. I said, “Well, it’s impossible to write a detailed history like you want that fast.” And Curtis said, “Ok if you can’t do it right away then we’ll get someone else who can.” I think they announced who their next writer would be, but the book never came out.

The other problem was that so many fans were hostile to the idea. In science fiction fandom even Sam Moskowitz, who was feuding with practically everybody when he announced he was doing his book, got lots of cooperation. Everybody sent him lots of information, and answered whatever questions he sent them. But when I was asking furry fans outside of Southern California for the history of furry fandom in their areas, which I was not personally involved with, they said “Why should we help you? We’ll write our own history that’d be better than anything you could do. We’ll refuse to give you the information, and when your book comes out without the information we’ll tell everybody how incomplete it is.” Someone accused me of being a phony furry fan because I did not wear a fursuit. So I reported to Shanda Fantasy Arts that any history I would write would be very incomplete. Actually, I could have tried to work around the obstructionists, but I was also getting more and more requests to write articles about anime and manga at the same time, and Shanda insisted on getting the furry history immediately, so I just gave up on it. Anyhow, the history that was in Best in Show was so brief that I was able to summarize without having to go into detail. I could just say there are a lot of furry activities such as fanzine publishing, fursuit making, holding conventions and so on, without having to give lots of names and dates.

Another sort of – I don’t know whether you would call this a problem or not in furry fandom, but more science fiction fans used their real names, or if they used nicknames their real names were pretty well known. Like you could say that Jack Bristol was really Jack Speer but he did most of his fan activities using the name of Jack Bristol. Ted Johnstone’s real name was David McDaniel. But too many of the furry fans have only their fannish names known; and obviously phony names at that. I at least would find it difficult to do a serious history about people who are only identified by names like Gizmo, Vixyy [sic.] Fox and Hyperwolf. So I guess that was another problem with writing a detailed history of furry fandom.

Yet another reason why it would have been very difficult to write a history of Furry Fandom comparable to the histories of s-f fandom in the 1930s and 1940s was that the s-f fans of that time were paper hoarders, not only of fanzines but of correspondence. When Moskowitz and Warner asked for historical information for their books, fans could loan them original letters and old fanzines that included names & dates, detailed convention reports six and eight pages long, and so forth. Too much of Furry Fandom’s history took place over the Internet and nobody has a “hard” record of it; and fans’ ideas of convention reports today is a one-page “I went to the con and it was a lot of fun”. My preliminary questions got too many answers of, “Gee, that happened a long time ago, and I don’t remember the details.”

Most of what I knew about furry fandom’s history is covered in my 1996 Chronology of Furry Fandom in Yarf! which is now on WikiFur. Since WikiFur started a couple of years ago, it has added historical details that I never knew. So a history of furry fandom is even more desirable today than it was ten years ago; but – especially since my stroke has put me into bed and made it impossible to juggle old fanzines, correspondence, conduct interviews, etc. – I am not the one to write it. Good luck, Joe.

Joe Strike, what has happened to your book on the history of furry fandom?

Fred Patten

I don’t know if Joe frequents this site, but I will alert him to this informative thread.

Here comes Joe’s book!

http://dogpatch.press/2016/12/19/book-furry-nation

Five years in the making! (Actually, *more* than 5 years.)

It’s unfortunate that WikiFur isn’t a reliable resource for information on Furry fandom. Anyone can add anything—including patent nonsense—to it, and the admins will let it remain in the interest of including all viewpoints (including ones which have no basis in reality).

It would be good to see an authoritative history of Furry fandom written, even though GreenReaper thinks it’s impossible.

GreenReaper thinks a lot of things, such as spinning for Democrats whilst going easy on Lupine Assassin and Crusader Cat.

Great going

I do have one question, how much did SF fandom influenced the beginnings of furry fandom.

(This is to settle a little argument on furtopia)

Well, the fandom formed out of people from multiple fandoms – science-fiction/fantasy, animation, anime, comics, role-playing gamers – I don’t think it’s possible to say that any were dominant over the others. However, science-fiction conventions were the most common non-house events that allowed furry fans to meet up with each other during the 1980s. So I wouldn’t say SF fandom so much influenced furry fandom; it’s more along the lines of helping to provide the fandom with convenient places and times to meet up, depending what part of the country you lived in.

If you were a furry fan during the late 70s or early 80s, furry hadn’t come together as a fandom yet. With no Internet, you were on your own in terms of your obscure interest. You weren’t a furry fan; you were an animation fan, or an RPG fan, or a SF fan, etc. – and a nerd who also happened to like anthropomorphic animals, which thanks to Disney and Saturday morning cartoons, were considered kid’s stuff.

And since you weren’t going to find much besides kid’s stuff in popular culture, you went to where other nerds hung out: comic book stores, RPG sessions, science-fiction conventions, and local clubs (if any). You had to be able to travel a bit and be socially competent/outgoing. Because at the nerdy gatherings, you knew there was just a slightly higher chance of finding anthropomorphic stuff, aimed at an older age group. But mostly you went to these places because you liked comics or SF or gaming or whatever. And then, usually completely by accident, you figured out someone else there thought anthropomorphics were cool too – and slowly, very slowly, that’s how folks met and things started to come together.

I would say that SF fandom influenced THE BEGINNINGS of furry fandom a lot. Ken Fletcher, Marc Schirmeister, Mark Merlino, Steve Gallacci, Timothy Fay, Ken Sample, Taral Wayne, myself, and other “founders of furry fandom” were already very active in SF Fandom. The first meetings of furry fans were held at SF conventions, and at comic book conventions which were heavily influenced by the SF conventions. The first Furry Parties were held at SF conventions, and the first four or five Furry conventions were modeled upon the SF conventions. After 1992 or 1993, furry fandom was flooded by new fans brought in by the Internet, particularly Fursuiters, who were not familiar with SF fandom and who led furry fandom in new directions.

Fred Patten

And the late 80s brought in a lot of people from the comics and zine crowd, too.

And then the Internet came, and destroyed everything 😀

Well, I’ll be…

I’ve been getting E-mails from friends who think this was ripped off from me. But of course Fred did his original Yarf Chronology first, and it was an important reference in creating my own Furry History Project. Fred has even contributed a few items to my project recently.

I must admit that this does look a lot more like my project now that it has illustrations, and a number of the items that were added were ones that I featured first. So it does leave me feeling a bit let down that I didn’t rate even an honorable mention as some form of contributor.

Sadly, since Furtopia hosting went poof and my project has been hosted on Live Journal, no one seems to care about it anymore. Or maybe it’s just grown too big for even the most interested of Furries to want to read that much.

For anyone who’s interested in seeing the expanded history of the Furry interest, or anyone who might like to contribute to the project, it still exists and is located at the link below.

http://spectralshadows.livejournal.com/46979.html

I glanced at that once, I think during the debate on defining furry. It is a lot to read but I would like to at some point. I feel like I should point out that that background is not conducive to easy reading.

“If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

~John Stuart Mill~

I killed the background. If anyone would like to build a proper website and presentation for this information, let me know.

I have finished my retrospective on the Roosevelt Bears books by Seymour Eaton (1859-1916), but GreenReaper already has other long articles by me on more popular Furry topics, to connect illustrations to, to put up first; so it may be several months before this goes online. Judging from “Talking Animals in World War II Propaganda” and this Chronology, it takes GreenReaper about a month to connect all the illustrations to one of these long articles. In the meantime, if anyone wants to know anything about the Roosevelt Bears, ask me.

Fred Patten

I’ll be very interested in linking to that. The best I could find was a section in the middle of a longer piece on Teddy Bears. But I have entered the items you suggested, with illustrations and links where possible. See here. http://spectralshadows.livejournal.com/45269.html

Very good! The frustrating thing about this article is that many of the weblinks to Roosevelt Bears cover illustrations are from eBay auctions, which are only temporary until the auction ends and are often taken down before they can be linked to this article. I will send it to GreenReaper (who should be reading this), and maybe he can put the text online so you can link to it, and connect the illustrations later.

My parents introduced me to the Roosevelt Bears books in the early 1940s, from their own tattered childhood copies. I loved them, and I was traumatized to find that they were already long-forgotten and that libraries and bookstores could no longer provide additional titles. Researching and writing this article has been like therapy for me.

Fred Patten

You should also write an article about growing up in the Furry 40’s. We don’t often get to hear that perspective. I’d be very interested to hear what other Furry stuff you liked back then and how you felt about it.

“the Furry 40’s”? They weren’t, very. It was not until Furry Fandom started in the 1980s that I was able to look back and realize that I had been a Furry fan all my life and had never realized it.

I was born in 1940. My parents gave me their old 1910s children’s books, which in addition to the Roosevelt Bears books that I’ve already told you about, included the Uncle Wiggily Longears books about “the gentleman rabbit”, and the Three Billy Goats Gruff books. I did not realize at the time how outdated they were, partly because both my parents worked during World War II and just after, and I was raised at home by my grandmother, who was more old-fashioned than any of us had suspected. I started in elementary school in 1947, and was bewildered by my schoolmates’ talk about what their fathers had done in “the War”. According to my grandmother, the War had ended when the Union Army occupied New Orleans in ’62. Once my parents realized what Gramma had been teaching me, they brought me up to the present, but we never did convince Gramma that the Union occupation of New Orleans in 1862 was not The End of the World.

“Everybody in New Orleans used to be SO POLITE, until the Union Army moved in and started ENFORCING the laws against dueling!”

I did real well in 19th century American history, though.

My parents taught me to read on the comic strips in the Los Angeles Times and Herald Examiner, and when I was four or five, they subscribed to Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories for me. I read anything that I could get my hands on (I was reading my father’s Philo Vance mysteries and my mother’s Perry Mason mysteries before I was given Dick and Jane in school), but the comic books that I picked out for myself were the funny animal titles. Besides the Disney comic books, there were the Looney Tunes comics (Bugs Bunny and the other Warner Bros. cartoon characters), Our Gang comics with Tom & Jerry and the MGM cartoon characters, Real Screen comics with the Fox and the Crow and other nominal Columbia funny animals (who I never saw in the movies), New Funnies comics with Woody Woodpecker, Oswald Rabbit, and the other Universal/Walter Lantz stars, several Terrytoons titles, and all the funny animal comic books not based on any movie studio’s licensed characters. Animal Comics with Pogo Possum and where Howard Garis had moved Uncle Wiggily to; the DC funny animal comics with the Dodo and the Frog, Nutsy Squirrel, and others; Giggle and Ha-Ha comics with Superkatt and Robespierre, also a cat (I later learned that they were written & drawn by moonlighting animation-studio cartoonists; Robespierre was by Disney’s Ken Hultgren, who later designed the Id Monster for “Forbidden Planet”), and obscure independent titles like ‘Red’ Rabbit (a funny-animal cowboy), Foxy Fagan, Super Duck, and more. My first “favorite character” who I wanted to grow up to be, when I was about five, was Sheldon Mayer’s Amster the Hamster – he could talk ANYbody into ANYthing! (Mayer also created Dizzy Dog, Doodles Duck, McSnertle the Turtle, The Three Mousketeers, Ferenc the Fencing Ferret, and others for DC comics; all childhood favorites. I was crushed when, in 1989, I got the chance to interview Mayer just before his death. I asked him why he particularly liked funny animals. He said that he didn’t; he thought they were stupid! But the editors at DC assigned him to write and draw them, so he did.)

There was nothing unusual about an under-ten boy liking funny animal comics. But I continued to like them after most boys had moved on to costumed-hero and horror comics.

At the public library, I guess that my favorite books were the animal fantasies, before I discovered science-fiction in 1950. Doctor Doolittle. Freddy the Pig. My favorites here were Robert Lawson’s children’s novels that mixed fantasy with s-f. The Fabulous Flight, with Sam the seagull who let a shrinking boy ride on his back. Mr. Twigg’s Mistake, about the mole, General DeGaulle, who grew bigger and bigger and bigger! Rabbit Hill, about a group of New England animals who worry that the new human family moving into the neighborhood may be the type who put out poison and go hunting. The novels that retold history from an animal’s viewpoint: Ben and Me (Ben Franklin and Amos Mouse), Captain Kidd’s Cat, I Discover Columbus (by his ship’s parrot), and Mr. Revere and I (by Paul Revere’s horse). I learned of Lawson’s death in the ’50s when I noticed that the copyright statement in his last novel had a tag, “The Estate of Robert Lawson”, pasted over it.

My parents got our first TV set in 1950, just in time for TV’s first funny animal cartoon, Crusader Rabbit (Los Angeles, September 1950). I was so frustrated that there were no Crusader Rabbit toys, like there were for all the Disney and WB and MGM cartoon animal stars! During my teens, kid’s TV became a dumping ground for all of the 1930s black-&-white theatrical cartoons that were never meant for just children. When I became active in early animation fandom in the 1970s, some fan was always saying, “Here’s a cartoon that hasn’t been seen by anyone since the 1930s!”, and he would show a ratty 16 mm. print of a WB cartoon that I saw many times on TV in the ‘50s, including all the Politically Incorrect ones.

But I always felt alone. My teachers and children’s librarians said that Robert Lawson’s books, and the Freddy the Pig books, were very popular, and I guess that they must have been or their publishers would not have kept printing new titles; but I never met anyone else who particularly liked them. In my teens I got more and more into s-f, then in the 1960s when costumed heroes made a comeback and comics fandom developed, I bought all the DC and Marvel titles like the other fans. But I also resumed buying and enjoying what funny animal comics were still out there. I thought that I was the only adult who still enjoyed the funny animals, until the 1980s when Furry Fandom came together.

Fred Patten

It sounds like you’d have been in a position to encounter the Thornton W. Burgess books, as well (the basis for that “Green Forest” cartoon that ran in the early ’80s up here). I encountered very old copies of the books at my grandmother’s house, and might actually have been given a few (they’re disintegrating now; the series started in 1914).

The timing was right, but the Los Angeles Public Library did not have anything by Thornton W. Burgess when I was a child. He was an author that I heard about but never read. The LAPL had a very rigid policy for “literature” but against “popular mass series” during my childhood. No Oz books; nothing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, no Thornton Burgess. No Palmer Cox, no Hardy Boys, no Nancy Drew. One of the first things that I did when I became a student at UCLA in 1958 and got access to the UCLA Research Library was to read everything by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Then UCLA’s set of bound issues of Astounding Science Fiction going back to the earliest Street & Smith issues in 1933. I later realized that even if the Roosevelt Bears books had still been available in the 1940s, the LAPL would never have gotten them because they “were not literature; they were just mass-market series books”.

Fred Patten

One thing I was specifically curious about was if you remembered Furry characters on the radio in the 1940’s. I started collecting Old Time Radio when I was 10 in 1972. (My first official participation in a fandom.) Furry pickings are rather slim in that fandom, but things like The Cinnamon Bear and Wormwood Forest are naturally a big deal for me. I hardly ever run into any other furs who know about these titles.

I also collect Furry children’s records from that era, one of which I have on 78’s is “Captain Kidd’s Cats.” I also have one of Uncle Wiggly, the original Rudolph The Red Nosed Reindeer album that the cartoon was based on, and numerous other early examples.